5. What to do: response options

Shelter programmes should support people’s own preferences and approaches to finding shelter.

Families and communities find shelter after a natural disaster or conflict in a number of different manners. The situation and the needs will vary from one location to another, depending on whether people are displaced or not displaced, on their resources and capacities, and on many other factors. It is also important to understand the likely manner in which a community will recover – what is its probable ‘pathway to recovery’?

The needs assessment should identify these different spontaneous shelter options. Some of the most common are considered below:

Temporary or makeshift shelters

Very sub-standard and basic shelters made from salvaged materials, plastic sheeting, rope, etc. This is never considered to be an adequate or appropriate solution, even in the short-term. The rapid needs assessment should identify the needs of these families so that emergency support can be provided.

Host families

People may stay with host families if they have relations or friends. This can be a good way to stay connected with existing community networks and to access resources. Alternatively, they may pay rent and live with strangers. People staying with host families can be missed during assessments because their situation is not visible. Overcrowding and privacy can be an issue with unsupported host families.

It is important to assess the needs of both hosted and hosting families.

Collective Centres

In the first instance after a disaster, a collective centre is likely to be a community building such as a school, church, hall etc. Destitute families will sleep communally, often in very crowded conditions with inadequate privacy and access to water and sanitation. A shelter programme can support these families with NFIs and materials to improve privacy and dignity. However there is often pressure to vacate collective centres as quickly as possible so that they can revert to their original use, classes can commence etc. Collective centres can also be purpose-built, normally by the government. Generally CARE would consider then to be an option of last resort.

Informal or spontaneous camps

Families that cannot either build a basic shelter, repair their existing house or move-in with another family will be forced to set up informal camps, sometimes within their home community, but sometimes migrating considerable distances. The assessment needs to locate these camps – they can be as small as just one family – and ascertain their emergency and longer-term needs.

Rentals

Displaced people who have the resources to do so may seek to rent land or accommodation in the short or longer term.

Self-recovery

Frequently families initiate a rapid pace of reconstruction and repair and use the resources they have to hand. This might be done in parallel with temporary shelter or hosting, or accommodation in a collective centre.

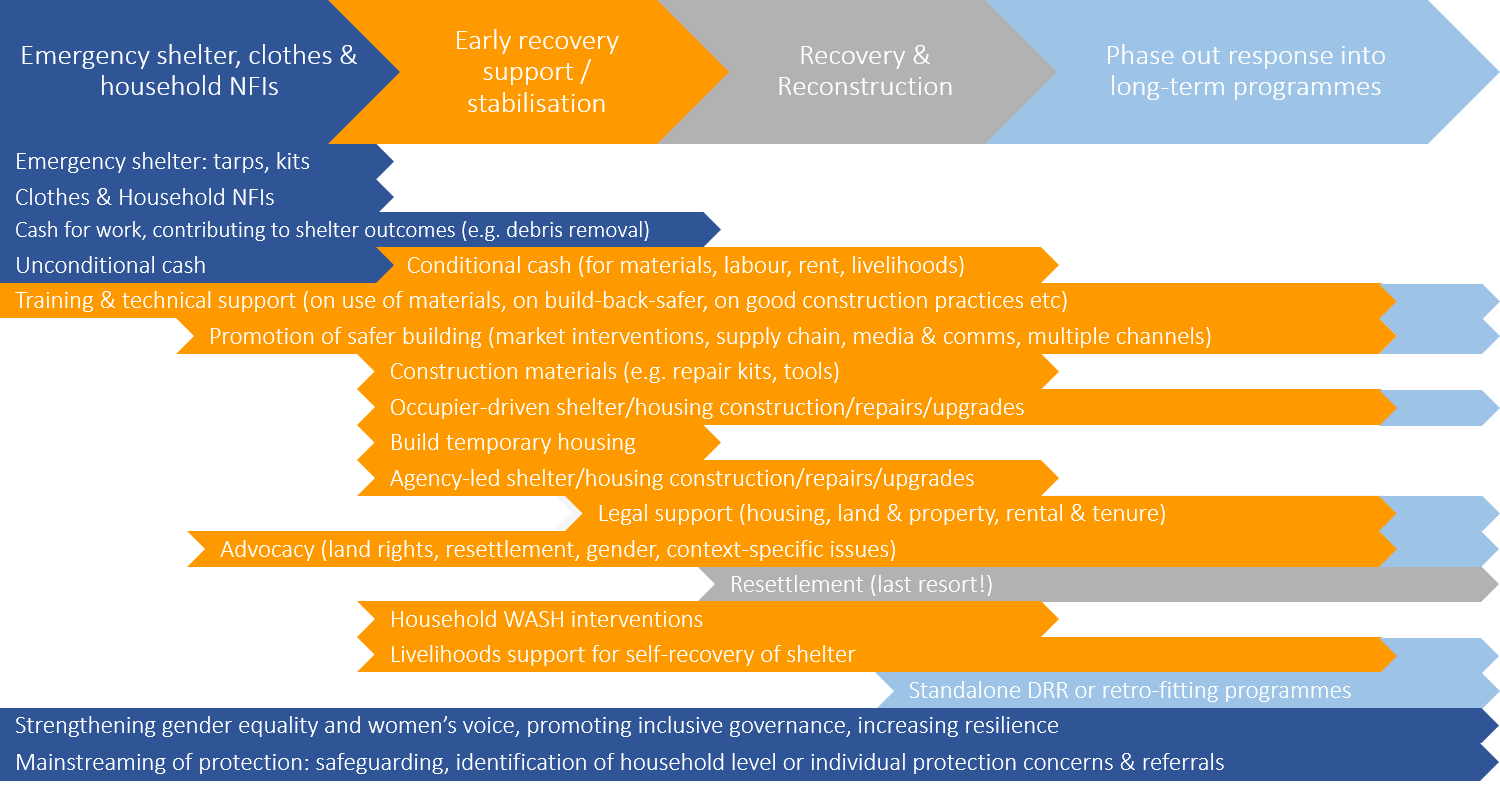

Depending on the way in which people are seeking to shelter themselves, their plans for recovery, and the capacity of their communities and local organisations to support them, there is a wide range of shelter support options open to CARE and its partners:

Emergency shelter kits

An emergency shelter kit contains as a minimum:

- 2 plastic sheets (tarpaulins), 6m x 4m, or 7m x 4m.

- Rope, polypropylene, 6mm x 40m

An emergency shelter kit may also include:

- Tools (shovel, hammer, handsaw, hoe, shears etc.),

- Fixings (nails, tie wire, rope tensioners, etc)

The use of emergency shelter kits assumes that suitable framing materials or structures are available to fix the plastic sheets to. If these are not available, or obtaining them locally will cause significant environmental damage, two or more 2m long wooden or metal poles may be provided with the kit.

DFID and IFRC have standard emergency shelter kits. See Selecting NFIs for shelter and the IFRC Shelter Kit Guidelines.

Most items, apart from the plastic sheeting, will probably be available in the local market and can be sourced in-country. Suitable specifications for all items listed in the shelter repair kit are available on the IFRC emergency items catalogue.

Plastic sheeting

Plastic sheeting is the main part of an emergency shelter kit. It is important that plastic sheeting provided by CARE is of a suitable specification. The plastic sheeting which is readily available in most markets is usually low quality and will not be durable enough to keep people safe and dry for the duration of their need for shelter.

See here for an excellent overview of why a suitable specification must be used.

Plastic sheeting should always be distributed alongside appropriate training and technical support in its use. As a minimum, information must be given on how to adequately fix plastic sheeting. A basic set of graphical instructions is available: IEC Fixing Plastic Sheeting

See the following videos for examples of best practices: J/P HRO & USAID/OFDA Emergency Shelter Program: Tarp Installation Best Practices in English, French, Haitian Creole, and with Spanish subtitles.

CARE maintains stocks of plastic sheeting in Dubai, and has access to free shipping. CARE Country Offices can contact the Emergency Shelter Team or Logistics Team to enquire about using the stocks.

CARE has master contracts in place for rapid international procurement of high quality plastic sheeting. Contact Joanne Rivera and Stephanie King at CARE USA for support on procurement and to place orders.

The specification for plastic sheeting to be used by CARE is:

- 301 – PLASTIC SHEETING – pre-punched – preferred spec

- 301 – PLASTIC SHEETING – eyelets – back-up spec (only if the preferred specification is not available).

The specifications are based on the IFRC specifications, which may also be used.

See Annex 25.10a, b & c for further guidance on the specification and use of plastic sheeting in humanitarian relief in English, French & Spanish respectively.

Tents

Tents are a common way of providing emergency shelter, but are bulky, expensive, difficult to repair and may not be durable enough for many situations. They are a good way to provide consistent and weather-proof shelter in a relatively quick time (note that lead times for delivery can be long though). Tents are also relatively easy to ‘winterise’, i.e. to insulate and keep warm in cold climates.

Tents have recently been developed which are fire-retardent. Fires in tents, especially in camp settings, are both common and highly dangerous. However, fire-retardent tents are currently significantly more expensive than non fire-retardent tents. The decision must be made on a case-by-case basis as to which is the most appropriate specification to choose. If non fire-retardent tents are procured it is essential there is a carefully designed and implemented fire risk management system in place, and occupants are given appropriate training in avoiding and dealing with fire.

CARE has master contracts in place for rapid procurement of family tents. Contact Joanne Rivera and Stephanie King at CARE USA for support on procurement and to place orders.

See Annex 25.12 for guidance on the use of tents in humanitarian contexts.

Emergency shelter kits or tents?

It is most often more cost-effective and relevant to use emergency shelter kits, rather than tents. For more information see the Tents or Tarpaulins Guidance Note:

Other shelter kits

Shelter fixing kit

Galvanised nails, roofing nails and tie wire are often among the most requested items as they allow families to rebuild using salvaged materials. These can be collected into a ‘fixing kit’ that complements the tools in the Emergency Shelter kit. Critical items that allow the family to comply with key build-back-safer messages – such as cyclone strapping – should certainly be considered.

The CARE UK shelter team can advise on suitable items and quantities to be included in the fixing kit.

Why not cash?

Wherever possible, it is better to give people cash, not stuff. Before deciding to give NFIs, answer these questions:

1. Why not cash?

2. And if not now, when?

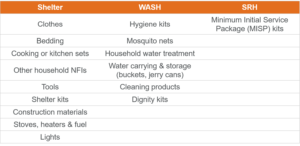

Non-food items (NFIs) are a very common emergency response modality. Household NFIs are normally considered to be part of the shelter sector, but not all NFIs are shelter. Support on choice, procurement and delivery of the different NFIs can be obtained from the relevant technical teams:

Shelter NFIs are most often distributed in kits, such as:

- Emergency shelter kits

- Winterisation kits

- Repair kits or fixing kits

- Cooking kits / kitchen sets

- Tool kits

- Household kits, or ‘general household support kits’

‘General household support kits’ often contain items from both shelter and WASH sectors. It is important that distribution of all items is supported with the necessary training on proper use, or hygiene promotion (e.g. jerry can cleaning). Contact the WASH team for support on WASH NFIs.

Selecting the right NFIs

NFI Technical Working groups are normally set up within the national shelter cluster or working group to discuss the technical aspects, specifications and adaptation of standard kits to the local preferences and needs in consultation with all sector partners.

It is important to think carefully about what NFIs are provided, and to whom. Women, men, girls and boys will all have specific needs, as will people with disabilities, elderly people and other groups. Gifts provided in kind by donors may not be appropriate, and should be treated with great caution. For more detailed guidance on what to consider when selecting NFIs see Selecting NFIs for Shelter.

As part of the Emergency Preparedness Planning (EPP) process, high risk Country Offices should design culturally- and gender-appropriate kits and pre-identify suppliers.

Cash transfer can be used as an integral part of different response modalities – in other words, cash fits well with self-recovery, an NFI winterisation programme or a number of other possibilities. It can be combined with some materials, tools and fixings. It is normally conditional, with the distribution divided into a number of tranches conditional on construction reaching a certain level and standard. It is rarely sufficient to rebuild a house, relying on the family to find the shortfall.

A cash response provides the beneficiary family with choice and ‘agency’. The cash can be spent on materials or labour according to their needs and wishes. It is important that specialist knowledge on cash programming is sought if the capacity does not exist in the CO.

For more on cash, visit the CALP website:

This publication by CRS has examples of cash programming:

https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/using-cash-for-shelter-an-overview-of-crs-programs/

Conditional Cash for Shelter

Cash can be a powerful tool for achieving shelter outcomes by giving project participants a greater role and agency in the process of reconstruction/repair/other shelter activities. Rather than employing expensive external contractors, we can establish systems to transfer cash tranches to households themselves so that they might directly manage the labour/logistics/material procurement themselves if they are in a position to do so and have access to local markets. Completing tranche technical conditions allow for the release of subsequent tranches moving participants though the process and breaking the work into manageable phases.

Vouchers

Vouchers are an alternative to cash often used for NFI distributions. The beneficiary is given a voucher that can be redeemed for specified items in previously identified shops. It limits choice, but provides a greater measure of control and reduces the risk of inflationary prices.

Shopping list or purchase plan

This has rarely been used in practice but may have potential if the conditions and circumstances are suitable. Each family makes a selection (a shopping list) from a previously designed list of shelter materials. CARE is then responsible for the collective purchase and delivery of the items to the family. This gives the advantage of lower prices and economic delivery through bulk purchasing. Individual families don’t have to make multiple trips to purchase materials.

Increasingly CARE is advocating an approach that supports the self-recovery process and technical assistance and the promotion of a few simple ‘build-back-safer’ messages is an essential component. However it is not confined to self-recovery programmes and can be an integral part of transitional shelter, construction, repair etc. At its heart is the need to closely accompany the community in the process of recovery to encourage the promotion of safer, better, more durable house construction. Training alone is rarely enough. Community accompaniment and household level support is essential. The technical accompaniment will frequently focus on the promotion of 4 or 5 key ‘build-back-safer’ messages that may be standardised through the cluster technical team.

Roving teams

A roving team consisting of community social mobilisers and technical advisors (also from the community) can support families in the construction of their homes and adherence to key build-back-safer messages. A gender balance is essential, preferably one that challenges the stereotype of construction being the man’s domain.

Information, Education & Communication (IEC) material

The cluster is likely to develop standard technical guidance in the form of printed sheets and posters. However the CARE team should give careful consideration to the most effective way of communicating given the complexity of some technical issues and possible varying level of literacy within the community. IEC material from a previous disaster response in a different context is most unlikely to be appropriate. There are two important elements: 1) what are the messages we wish to communicate and 2) what is the best approach to communicating those messages.

The affected families are always the first responders and the most important stakeholder. Inevitably recovery starts on the first day after a disaster and families start to rebuild without support from the international community, relying on their own resources. In many major disasters 80% or more of the affected population ‘self-recover’. CARE is a leading proponent of support to self-recovery and the shelter team at CARE UK can provide assistance to country offices if a self-recovery approach is considered appropriate. Some considerations of self-recovery are:

- The approach is likely to involve more enabling and less construction

- Each family will exercise choice in how, when and where they rebuild their homes

- Technical assistance, build-back-safer key messages and community accompaniment are key to leaving a lasting legacy of improved and safer construction.

- Sector integration and a holistic approach adds value – especially WASH and livelihoods

- The entire community can be considered, and not just a targeted selection of beneficiaries.

- A gender sensitive approach should always be employed, with attention to the empowerment of women and girls.

Sometimes referred to as t-shelters, temporary solutions are a common form of response. However consider carefully whether this is the most appropriate approach: it can be wasteful of resources that would otherwise be put towards a permanent solution and frequently ‘temporary’ houses become sub-standard permanent houses as families are unable to up-grade or rebuild. Quality and engineering standards are as important for temporary as they are for permanent houses.

It is unusual for CARE to carry out major house building programmes. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Lack of available funds

- With limited funds, the significance of a housing programme is reduced and normally limited to a small targeted beneficiary group.

- The economic benefit normally goes to a large contractor often outside of the disaster affected area.

- Quality is difficult to assure.

- It is difficult to build-in DRR and resilience, or to improve the capacity of the local builders.

If construction is deemed appropriate then there are different delivery options, each with a variety of pros and cons. These should be carefully evaluated:

- Direct labour – CARE will act as the contractor.

- Community labour – the community is responsible for the delivery.

- Contract labour – normally a contractor from outside the affected community.

- Self-build – this has similarities to self-recovery programming.

In all cases, it is considered preferable that an ‘owner-driven response’ is used.

Collective shelters are often used when displacement occurs inside a city, or when displaced people move to an urban area. However they are equally common in rural settings. They include existing structures, such as community centres, town halls, schools, disused factories and unfinished buildings. They can also be purpose-built (eg the ‘barracks’ in Aceh, after the Indian Ocean tsunami; ‘bunkhouses’ in the Philippines). Collective shelters are usually only appropriate for the short term while other settlement options are arranged. Collective shelters should have appropriate services and support, including conditions to ensure dignity, privacy and adequate sanitary conditions.

CARE may support communities in collective centres by:

- assessing the suitability of the building, and providing plans and materials to improve it, for example, dividing a school classroom into bedrooms

- providing cooking equipment, health care, water and sanitation services.

- supporting governments and communities in management of the sites.

See also this Guidance Notes for Delivering and Managing Collective Shelters (specifically for Syria, but much is applicable in other contexts).

Communities made homeless will settle where they can and will set up self-settled, informal camps if no other option is available. These camps are often small, on unsuitable sites with services that are often inadequate, overburdened or entirely absent. Self-settled camps can sometimes be overlooked by UN agencies and the government. Therefore, these camps often require support.

CARE may support displaced communities in camps by:

- providing self-settled camps with additional resources, where the site is deemed appropriate

- providing resources such as household items, construction materials, cash or vouchers to the camp population, preferably in situations where the local markets are functioning and accessible for the camp dwellers and to enable them to make a choice in meeting their priority needs or cover temporarily for a lack of income generating opportunities.

For further guidance see:

- Guidance Notes for Informal Tented Settlements Shelter Intervention Projects – CARE & UNHCR (Specifically for Syria, but much is applicable in other contexts).

It is important to consider housing, land and property rights in all shelter responses that go beyond basic emergency shelter. HLP is often very important in achieving gender responsive or gender transformative programming, and good HLP programming can lead to meaningful economic empowerment of women.

Guidance on integrating HLP in programmes can be found in

- Annex 25.4: CARE Good Shelter Programming Guidance

- Annex 25.16: Guidance Note: Integrating Housing, Land and Property Issues into Key Humanitarian, Transitional and Development Planning Processes, published by IOM.

At the outset of a response with a significant shelter component it is recommended that CARE invests in identifying and analysing HLP issues in the particular context, and establishing the role that NGOs can play in addressing them. For an example of this, see the report commissioned by CARE Nepal early in the 2015 earthquake response.

CARE can always support communities through advocacy, and typical issues requiring advocacy are:

- The right to transitional settlement

- A safe location with access to services

- An equitable and efficient compensation process

- Leadership, strategy and continuity of policy from those responsible for coordinating the response

- The right to return

- The right to own land

- Property restitution

- Appropriate and affordable building standards

- Access to materials and labour

- Property and land ownership in the names of male and female households

- Property and land ownership protection for vulnerable groups.

CARE can also provide legal assistance by ensuring there are fair and enforceable legal agreements between tenants, landlords, local authorities, or other stakeholders. Where these are not legally enforceable, there may be other ways to enforce agreements, such as community involvement. Specialist actors such as NRC’s ICLA may be available in some contexts for referrals, advice, or more detailed legal assistance in partnership with CARE.

Urban areas tend to have greater social diversity, higher levels of mobility and less social cohesion than rural areas. In cities the informal settlements populations can be composed of rural migrants, refugees and displaced people with different socio-cultural backgrounds. Chronic vulnerabilities of the poor urban residents may overlap with the on-going humanitarian needs of the internally displaced or refugee populations.

Neighbourhood, or area based, approaches have become increasingly recognised as a comprehensive modality for working in urban areas during or after a crisis. This seeks to offer a way of integrating different sector approaches at multiple levels in the community, involving a wide range of stakeholders, and strengthening sustainability of interventions by bringing closer together emergency, recovery, and longer term development support. CARE’s work in Lebanon on the Integrated Neighbourhood Approach (Captured in Guidelines and Reflection) is a detailed example of how this approach can be operationalised and contextualised for any given urban scenario.

In an urban context, area-based approaches typically share common characteristics: they target areas defined by socio-economic boundaries (rather than geographical limits), and they adopt a multi-sector and participatory approach. This should also be implemented on multiple levels –individual, household and community. For example, upgrades to housing are complemented by improvements of the neighbourhood infrastructure (water network, drainage and sewage systems, public lighting or electricity lines) and rehabilitation of communal areas and open spaces (footpaths, social gathering places, playgrounds, sport facilities…). The physical improvement of the built environment is just one aspect of the overall rehabilitation of the neighbourhood: livelihoods regeneration, GBV prevention, health and DRR are also addressed through vocational trainings and financial support to the small and medium enterprises, community engagement and awareness raising, capacity building of grassroots organisations and local authorities, participatory urban planning and legal support.

Although it is unrealistic to assume that a single organisation using a neighbourhood approach methodology can address all the infra-structure, social and economic needs in an area, interventions can still be multi-sector in addressing the most urgent needs (shelter, WASH and protection as a minimum). Coordination, partnerships with local and international NGOs, and public-private partnerships can go beyond individual assistance to include long-term activities that have a wider impact on the community and local institutions.

Key considerations for urban responses:

- The scale and complexity of urban disasters increases the need for effective partnerships with local civil society, local and national authorities, and humanitarian actors.

- Coordination is key in urban assessments, both with agencies and government authorities to ensure information sharing and a broader understanding of the context.

- ‘Community’ and ‘neighbourhood’ are not always the same thing. Needs may be widely dispersed and communities may be defined in other ways than geographic proximity, for example by family, social networks or communities of interest (ALNAP, 2012).

- Displaced populations and refugees are identified as some of the most vulnerable populations in urban centres due to lack of social networks, discrimination, stigmatization, exposure to harassment, threat of eviction, and, in the case of refugees, denial of right to work.

- Implementation of Cash Transfer initiatives with cash- and voucher-based systems will help revitalising local economies, supporting existing shops, vendors and producers.

- Housing land and property (HLP) rights are complex and may take longer than the project timeframe to be resolved.

- Community infrastructure projects may provide income-generating opportunities (in construction, rehabilitation, management, maintenance etc.). For example, community waste management and recycling initiatives, management of water provision and chlorination, maintenance of drainage systems, etc.

Adapted from:

Key references:

- RedR UK – Ready to Respond Skills gaps for responding to humanitarian crises in urban settings in the WASH and shelter sectors

- CARE Lebanon – ‘Beyond four walls and a Roof’ – Reflections on the One Neighbourhood Approach

- CARE Lebanon – Integrated Neighbourhood Approach Guidelines

- Urban Multi Sector Rapid Needs Questionnaire 2018 (Kobo Toolbox)

- Neighbourhood Approach Example Indicators

- Conflict Sensitivity Analysis Diagram

This can be either for the host or hosted family, or both and may include:

- Distribution of household items , materials and/or shelter kits that allow the families to create more habitable space and improved conditions for privacy

- Housing upgrades to improve comfort, safety and privacy

- Rent-subsidies or cash-assistance to compensate for increased utility fees or for lost income-generating assets

Care should be taken to ensure equal support to both hosting and hosted communities and a ‘do no harm’ approach to minimise social tensions. The influx of displaced populations to densely populated areas can exacerbate the existing vulnerabilities of the host communities and lead to heightened social tensions due to overpopulation, lack of or limited access to adequate health/education facilities, strain on already deteriorated or substandard public services (water, sanitation, electricity etc.) – particularly in urban contexts. Integrated approaches for shelter, WASH, livelihoods support and protection are increasingly endorsed by Global Shelter Cluster leads and partners as a best practice in urban specific responses when assisting the host communities and displaced populations. These interventions may include upgrading of basic services and WASH systems, provision of vocational training and other forms of livelihoods support to increase access to income-generating opportunities.

For more on host community support see:

- Guidance Notes for Delivering and Managing Host Family Private Households – CARE & UNHCR (specifically for Syria, but much is applicable in many other contexts)

- Assisting Host Families & Communities – IFRC

There is often a need to up-grade shelters in harsh winter environments. This needs to be anticipated well in advance. At its simplest, it can be cash, voucher or NFI distributions to allow families to procure clothes, blankets, mattresses, fuel etc to protect themselves from the cold. A more comprehensive winterisation programme includes materials to up-grade, insulate and draught-proof a dwelling. Some winterisation information developed for the 2015 Nepal earthquake can be found here:

https://www.sheltercluster.org/sites/default/files/docs/infosheet-iom_winterisation_kit_003.pdf